Fruit Classification Using A Convolutional Neural Network

In this project we build & optimise a Convolutional Neural Network to classify images of fruits, with the goal of helping a grocery retailer enhance & scale their sorting & delivery processes.

Table of contents

- 00. Project Overview

- 01. Data Overview

- 02. Data Pipeline

- 03. CNN Overview

- 04. Baseline Network

- 05. Tackling Overfitting With Dropout

- 06. Image Augmentation

- 07. Hyper-Parameter Tuning

- 08. Transfer Learning

- 09. Overall Results Discussion

- 10. Next Steps & Growth

Project Overview

Context

Our client had an interesting proposal put forward to them, and requested our help to assess whether it was viable.

At a recent tech conference, they spoke to a contact from a robotics company that creates robotic solutions that help other businesses scale and optimise their operations.

Their representative mentioned that they had built a prototype for a robotic sorting arm that could be used to pick up and move products off a platform. It would use a camera to “see” the product, and could be programmed to move that particular product into a designated bin, for further processing.

The only thing they hadn’t figured out was how to actually identify each product using the camera, so that the robotic arm could move it to the right place.

We were asked to put forward a proof of concept on this - and were given some sample images of fruits from their processing platform.

If this was successful and put into place on a larger scale, the client would be able to enhance their sorting & delivery processes.

Actions

We utilise the Keras Deep Learning library for this task.

We start by creating our pipeline for feeding training & validation images in batches, from our local directory, into the network. We investigate & quantify predictive performance epoch by epoch on the validation set, and then also on a held-back test set.

Our baseline network is simple, but gives us a starting point to refine from. This network contains 2 Convolutional Layers, each with 32 filters and subsequent Max Pooling Layers. We have a single Dense (Fully Connected) layer following flattening with 32 neurons followed by our output layer. We apply the relu activation function on all layers, and use the adam optimizer.

Our first refinement is to add Dropout to tackle the issue of overfitting which is prevalent in the baseline network performance. We use a dropout rate of 0.5.

We then add in Image Augmentation to our data pipeline to increase the variation of input images for the network to learn from, resulting in a more robust results as well as also address overfitting.

With these additions in place, we utlise keras-tuner to optimise our network architecture & tune the hyperparameters. The best network from this testing contains 3 Convolutional Layers, each followed by Max Pooling Layers. The first Convolutional Layer has 96 filters, the second & third have 64 filters. The output of this third layer is flattened and passed to a single Dense (Fully Connected) layer with 160 neurons. The Dense Layer has Dropout applied with a dropout rate of 0.5. The output from this is passed to the output layer. Again, we apply the relu activation function on all layers, and use the adam optimizer.

Finally, we utilise Transfer Learning to compare our network’s results against that of the pre-trained VGG16 network.

Results

We have made some huge strides in terms of making our network’s predictions more accurate, and more reliable on new data.

Our baseline network suffered badly from overfitting - the addition of both Dropout & Image Augmentation elimited this almost entirely.

In terms of Classification Accuracy on the Test Set, we saw:

- Baseline Network: 75%

- Baseline + Dropout: 85%

- Baseline + Image Augmentation: 93%

- Optimised Architecture + Dropout + Image Augmentation: 95%

- Transfer Learning Using VGG16: 98%

Tuning the networks architecture with Keras-Tuner gave us a great boost, but was also very time intensive - however if this time investment results in improved accuracy then it is time well spent.

The use of Transfer Learning with the VGG16 architecture was also a great success, in only 10 epochs we were able to beat the performance of our smaller, custom networks which were training over 50 epochs. From a business point of view we also need to consider the overheads of (a) storing the much larger VGG16 network file, and (b) any increased latency on inference.

Growth/Next Steps

The proof of concept was successful, we have shown that we can get very accurate predictions albeit on a small number of classes. We need to showcase this to the client, discuss what it is that makes the network more robust, and then look to test our best networks on a larger array of classes.

Transfer Learning has been a big success, and was the best performing network in terms of classification accuracy on the Test Set - however we still only trained for a small number of epochs so we can push this even further. It would be worthwhile testing other available pre-trained networks such as ResNet, Inception, and the DenseNet networks.

Data Overview

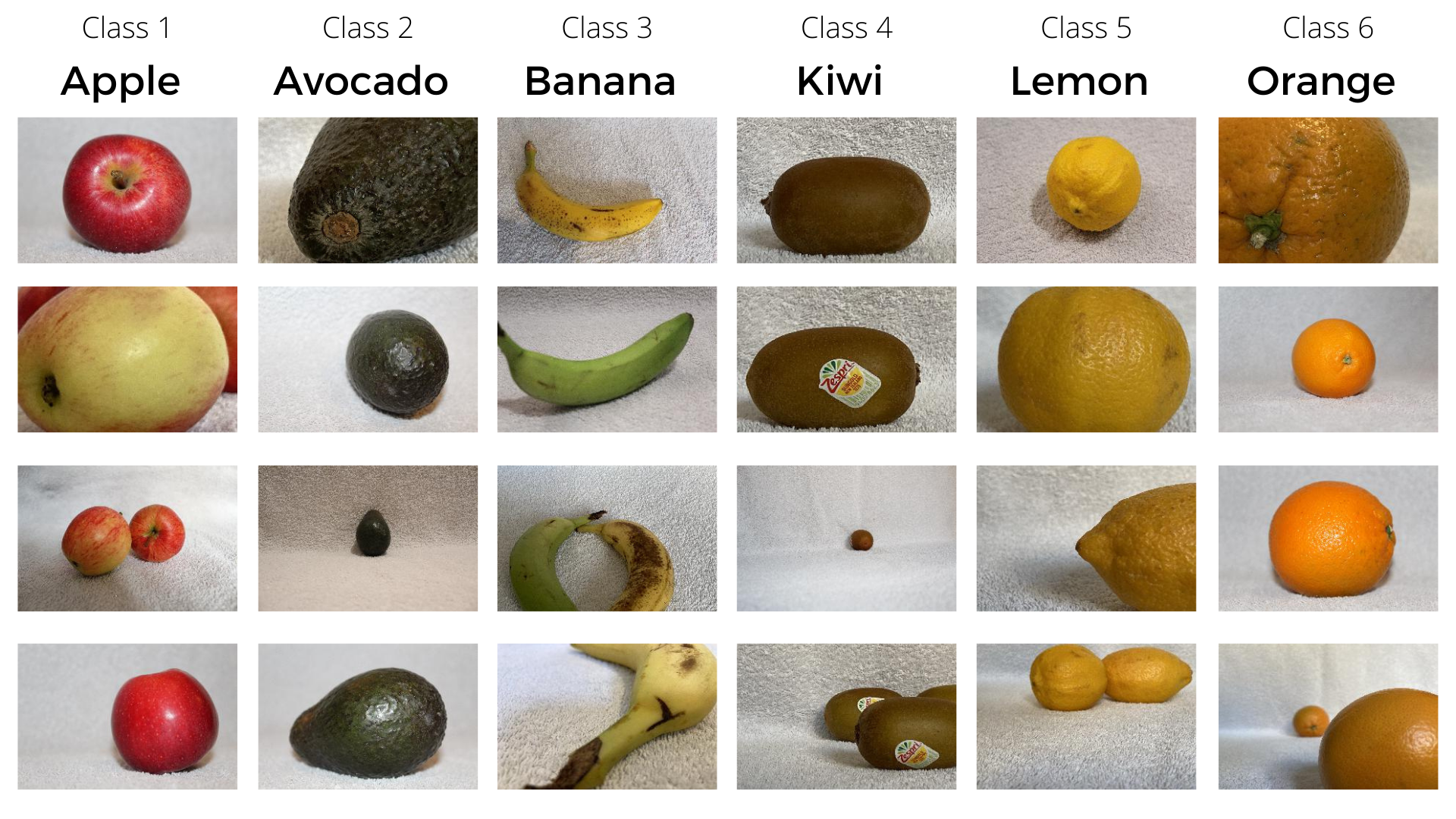

To build out this proof of concept, the client have provided us some sample data. This is made up of images of six different types of fruit, sitting on the landing platform in the warehouse.

We randomly split the images for each fruit into training (60%), validation (30%) and test (10%) sets.

Examples of four images of each fruit class can be seen in the image below:

For ease of use in Keras, our folder structure first splits into training, validation, and test directories, and within each of those is split again into directories based upon the six fruit classes.

All images are of size 300 x 200 pixels.

Data Pipeline

Before we get to building the network architecture, & subsequently training & testing it - we need to set up a pipeline for our images to flow through, from our local hard-drive where they are located, to, and through our network.

In the code below, we:

- Import the required packages

- Set up the parameters for our pipeline

- Set up our image generators to process the images as they come in

- Set up our generator flow - specifying what we want to pass in for each iteration of training

# import the required python libraries

from tensorflow.keras.models import Sequential

from tensorflow.keras.layers import Conv2D, MaxPooling2D, Activation, Flatten, Dense

from tensorflow.keras.preprocessing.image import ImageDataGenerator

from tensorflow.keras.callbacks import ModelCheckpoint

# data flow parameters

training_data_dir = 'data/training'

validation_data_dir = 'data/validation'

batch_size = 32

img_width = 128

img_height = 128

num_channels = 3

num_classes = 6

# image generators

training_generator = ImageDataGenerator(rescale = 1./255)

validation_generator = ImageDataGenerator(rescale = 1./255)

# image flows

training_set = training_generator.flow_from_directory(directory = training_data_dir,

target_size = (img_width, img_height),

batch_size = batch_size,

class_mode = 'categorical')

validation_set = validation_generator.flow_from_directory(directory = validation_data_dir,

target_size = (img_width, img_height),

batch_size = batch_size,

class_mode = 'categorical')

We specify that we will resize the images down to 128 x 128 pixels, and that we will pass in 32 images at a time (known as the batch size) for training.

To start with, we simply use the generators to rescale the raw pixel values (ranging between 0 and 255) to float values that exist between 0 and 1. The reason we do this is mainly to help Gradient Descent find an optimal, or near optional solution each time much more efficiently - in other words, it means that the features that are learned in the depths of the network are of a similar magnitude, and the learning rate that is applied to descend down the loss or cost function across many dimensions, is somewhat proportionally similar across all dimensions - and long story short, means training time is faster as Gradient Descent can converge faster each time!

We will add more logic to the training set generator to apply Image Augmentation.

With this pipeline in place, our images will be extracted, in batches of 32, from our hard-drive, where they’re being stored and sent into our model for training!

Convolutional Neural Network Overview

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) are an adaptation of Artificial Neural Networks and are primarily used for image based tasks.

To a computer, an image is simply made up of numbers, those being the colour intensity values for each pixel. Colour images have values ranging between 0 and 255 for each pixel, but have three of these values, for each - one for Red, one for Green, and one for Blue, or in other words the RGB values that mix together to make up the specific colour of each pixel.

These pixel values are the input for a Convolutional Neural Network. It needs to make sense of these values to make predictions about the image, for example, in our task here, to predict what the image is of, one of the six possible fruit classes.

The pixel values themselves don’t hold much useful information on their own - so the network needs to turn them into features much like we do as humans.

A big part of this process is called Convolution where each input image is scanned over, and compared to many different, and smaller filters, to compress the image down into something more generalised. This process not only helps reduce the problem space, it also helps reduce the network’s sensitivy to minor changes, in other words to know that two images are of the same object, even though the images are not exactly the same.

A somewhat similar process called Pooling is also applied to faciliate this generalisation even further. A CNN can contain many of these Convolution & Pooling layers - with deeper layers finding more abstract features.

Similar to Artificial Neural Networks, Activation Functions are applied to the data as it moves forward through the network, helping the network decide which neurons will fire, or in other words, helping the network understand which neurons are more or less important for different features, and ultimately which neurons are more or less important for the different output classes.

Over time - as a Convolutional Neural Network trains, it iteratively calculates how well it is predicting on the known classes we pass it (known as the loss or cost, then heads back through in a process known as Back Propagation to update the paramaters within the network, in a way that reduces the error, or in other words, improves the match between predicted outputs and actual outputs. Over time, it learns to find a good mapping between the input data, and the output classes.

There are many parameters that can be changed within the architecture of a Convolutional Neural Network, as well as clever logic that can be included, all which can affect the predictive accuracy. We will discuss and put in place many of these below!

Baseline Network

Network Architecture

Our baseline network is simple, but gives us a starting point to refine from. This network contains 2 Convolutional Layers, each with 32 filters and subsequent Max Pooling Layers. We have a single Dense (Fully Connected) layer following flattening with 32 neurons followed by our output layer. We apply the relu activation function on all layers, and use the adam optimizer.

# network architecture

model = Sequential()

model.add(Conv2D(filters = 32, kernel_size = (3, 3), padding = 'same', input_shape = (img_width, img_height, num_channels)))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(MaxPooling2D())

model.add(Conv2D(filters = 32, kernel_size = (3, 3), padding = 'same'))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(MaxPooling2D())

model.add(Flatten())

model.add(Dense(32))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(Dense(num_classes))

model.add(Activation('softmax'))

# compile network

model.compile(loss = 'categorical_crossentropy',

optimizer = 'adam',

metrics = ['accuracy'])

# view network architecture

model.summary()

The below shows us more clearly our baseline architecture:

Model: "sequential"

_________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

=================================================================

conv2d (Conv2D) (None, 128, 128, 32) 896

_________________________________________________________________

activation (Activation) (None, 128, 128, 32) 0

_________________________________________________________________

max_pooling2d (MaxPooling2D) (None, 64, 64, 32) 0

_________________________________________________________________

conv2d_1 (Conv2D) (None, 64, 64, 32) 9248

_________________________________________________________________

activation_1 (Activation) (None, 64, 64, 32) 0

_________________________________________________________________

max_pooling2d_1 (MaxPooling2 (None, 32, 32, 32) 0

_________________________________________________________________

flatten (Flatten) (None, 32768) 0

_________________________________________________________________

dense (Dense) (None, 32) 1048608

_________________________________________________________________

activation_2 (Activation) (None, 32) 0

_________________________________________________________________

dense_1 (Dense) (None, 6) 198

_________________________________________________________________

activation_3 (Activation) (None, 6) 0

=================================================================

Total params: 1,058,950

Trainable params: 1,058,950

Non-trainable params: 0

_________________________________________________________________

Training The Network

With the pipeline, and architecture in place - we are now ready to train the baseline network!

In the below code we:

- Specify the number of epochs for training

- Set a location for the trained network to be saved (architecture & parameters)

- Set a ModelCheckPoint callback to save the best network at any point during training (based upon validation accuracy)

- Train the network and save the results to an object called history

# training parameters

num_epochs = 50

model_filename = 'models/fruits_cnn_v01.h5'

# callbacks

save_best_model = ModelCheckpoint(filepath = model_filename,

monitor = 'val_accuracy',

mode = 'max',

verbose = 1,

save_best_only = True)

# train the network

history = model.fit(x = training_set,

validation_data = validation_set,

batch_size = batch_size,

epochs = num_epochs,

callbacks = [save_best_model])

The ModelCheckpoint callback that has been put in place means that we do not just save the final network at epoch 50, but instead we save the best network, in terms of validation set performance - from any point during training. In other words, at the end of each of the 50 epochs, Keras will assess the performance on the validation set and if is has not seen any improvement in performance it will do nothing. If it does see an improvement however, it will update the network file that is saved on our hard-drive.

Analysis Of Training Results

As we saved our training process to the history object, we can now analyse the performance (Classification Accuracy, and Loss) of the network epoch by epoch.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# plot validation results

fig, ax = plt.subplots(2, 1, figsize=(15,15))

ax[0].set_title('Loss')

ax[0].plot(history.epoch, history.history["loss"], label="Training Loss")

ax[0].plot(history.epoch, history.history["val_loss"], label="Validation Loss")

ax[1].set_title('Accuracy')

ax[1].plot(history.epoch, history.history["accuracy"], label="Training Accuracy")

ax[1].plot(history.epoch, history.history["val_accuracy"], label="Validation Accuracy")

ax[0].legend()

ax[1].legend()

plt.show()

# get best epoch performance for validation accuracy

max(history.history['val_accuracy'])

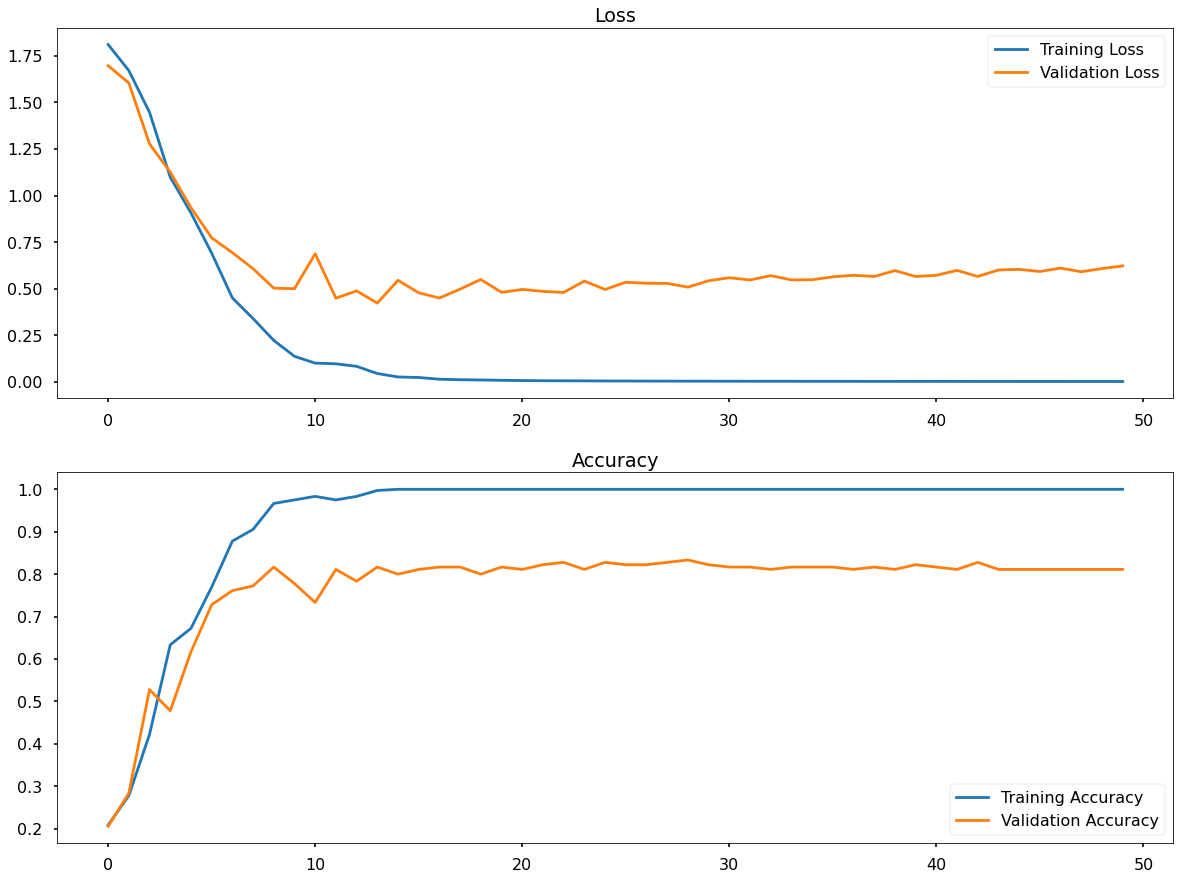

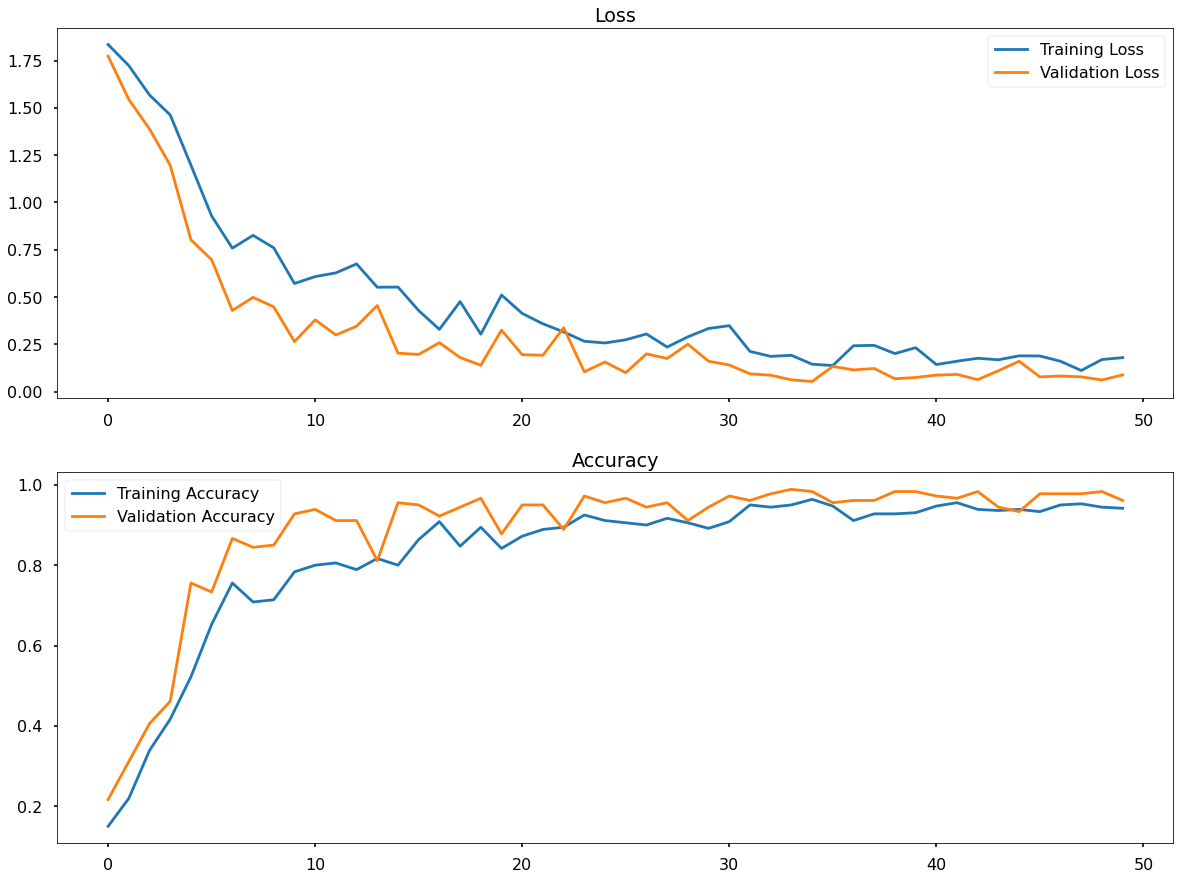

The below image contains two plots, the first showing the epoch by epoch Loss for both the training set (blue) and the validation set (orange) & the second show the epoch by epoch Classification Accuracy again, for both the training set (blue) and the validation set (orange).

There are two key learnings from above plots. The first is that, with this baseline architecture & the parameters we set for training, we are reaching our best performance in around 10-20 epochs - after that, not much improvement is seen. This isn’t to say that 50 epochs is wrong, especially if we change our network - but is interesting to note at this point.

The second thing to notice is very important and that is the significant gap between orange and blue lines on the plot, in other words between our validation performance and our training performance.

This gap is over-fitting.

Focusing on the lower plot above (Classification Accuracy) - it appears that our network is learning the features of the training data so well that after about 20 or so epochs it is perfectly predicting those images - but on the validation set, it never passes approximately 83% Classification Accuracy.

We do not want over-fitting! It means that we’re risking our predictive performance on new data. The network is not learning to generalise, meaning that if something slightly different comes along then it’s going to really, really struggle to predict well, or at least predict reliably!

We will look to address this with some clever concepts, and you will see those in the next sections.

Performance On The Test Set

Above, we assessed our models performance on both the training set and the validation set - both of which were being passed in during training.

Here, we will get a view of how well our network performs when predict on data that was no part of the training process whatsoever - our test set.

A test set can be extremely useful when looking to assess many different iterations of a network we build. Where the validation set might be sent through the model in slightly different orders during training in order to assess the epoch by epoch performance, our test set is a static set of images. Because of this, it makes for a really good baseline for testing the first iteration of our network versus any subsequent versions that we create, perhaps after we refine the architecture, or add any other clever bits of logic that we think might help the network perform better in the real world.

In the below code we run this in isolation from training. We:

- Import the required packages for importing & manipulating our test set images

- Set up the parameters for the predictions

- Load in the saved network file from training

- Create a function for preprocessing our test set images in the same way that training & validation images were

- Create a function for making predictions, returning both predicted class label, and predicted class probability

- Iterate through our test set images, preprocessing each and passing to the network for prediction

- Create a Pandas DataFrame to hold all prediction data

# import required packages

from tensorflow.keras.models import load_model

from tensorflow.keras.preprocessing.image import load_img, img_to_array

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from os import listdir

# parameters for prediction

model_filename = 'models/fruits_cnn_v01.h5'

img_width = 128

img_height = 128

labels_list = ['apple', 'avocado', 'banana', 'kiwi', 'lemon', 'orange']

# load model

model = load_model(model_filename)

# image pre-processing function

def preprocess_image(filepath):

image = load_img(filepath, target_size = (img_width, img_height))

image = img_to_array(image)

image = np.expand_dims(image, axis = 0)

image = image * (1./255)

return image

# image prediction function

def make_prediction(image):

class_probs = model.predict(image)

predicted_class = np.argmax(class_probs)

predicted_label = labels_list[predicted_class]

predicted_prob = class_probs[0][predicted_class]

return predicted_label, predicted_prob

# loop through test data

source_dir = 'data/test/'

folder_names = ['apple', 'avocado', 'banana', 'kiwi', 'lemon', 'orange']

actual_labels = []

predicted_labels = []

predicted_probabilities = []

filenames = []

for folder in folder_names:

images = listdir(source_dir + '/' + folder)

for image in images:

processed_image = preprocess_image(source_dir + '/' + folder + '/' + image)

predicted_label, predicted_probability = make_prediction(processed_image)

actual_labels.append(folder)

predicted_labels.append(predicted_label)

predicted_probabilities.append(predicted_probability)

filenames.append(image)

# create dataframe to analyse

predictions_df = pd.DataFrame({"actual_label" : actual_labels,

"predicted_label" : predicted_labels,

"predicted_probability" : predicted_probabilities,

"filename" : filenames})

predictions_df['correct'] = np.where(predictions_df['actual_label'] == predictions_df['predicted_label'], 1, 0)

After running the code above, we end up with a Pandas DataFrame containing prediction data for each test set image. A random sample of this can be seen in the table below:

| actual_label | predicted_label | predicted_probability | filename | correct |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| apple | lemon | 0.700764 | apple_0034.jpg | 0 |

| avocado | avocado | 0.99292046 | avocado_0074.jpg | 1 |

| orange | orange | 0.94840413 | orange_0004.jpg | 1 |

| banana | lemon | 0.87131584 | banana_0024.jpg | 0 |

| kiwi | kiwi | 0.66800004 | kiwi_0094.jpg | 1 |

| lemon | lemon | 0.8490372 | lemon_0084.jpg | 1 |

In our data we have:

- Actual Label: The true label for that image

- Prediction Label: The predicted label for the image (from the network)

- Predicted Probability: The network’s perceived probability for the predicted label

- Filename: The test set image on our local drive (for reference)

- Correct: A flag showing whether the predicted label is the same as the actual label

This dataset is extremely useful as we can not only calculate our classification accuracy, but we can also deep-dive into images where the network was struggling to predict and try to assess why - leading to us improving our network, and potentially our input data!

Test Set Classification Accuracy

Using our DataFrame, we can calculate our overall Test Set classification accuracy using the below code:

# overall test set accuracy

test_set_accuracy = predictions_df['correct'].sum() / len(predictions_df)

print(test_set_accuracy)

Our baseline network achieves a 75% Classification Accuracy on the Test Set. It will be interesting to see how much improvement we can this with additions & refinements to our network.

Test Set Confusion Matrix

Overall Classification Accuracy is very useful, but it can hide what is really going on with the network’s predictions!

As we saw above, our Classification Accuracy for the whole test set was 75%, but it might be that our network is predicting extremely well on apples, but struggling with Lemons as for some reason it is regularly confusing them with Oranges. A Confusion Matrix can help us uncover insights like this!

We can create a Confusion Matrix with the below code:

# confusion matrix (percentages)

confusion_matrix = pd.crosstab(predictions_df['predicted_label'], predictions_df['actual_label'], normalize = 'columns')

print(confusion_matrix)

This results in the following output:

actual_label apple avocado banana kiwi lemon orange

predicted_label

apple 0.8 0.0 0.0 0.1 0.0 0.1

avocado 0.0 1.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

banana 0.0 0.0 0.2 0.1 0.0 0.0

kiwi 0.0 0.0 0.1 0.7 0.0 0.0

lemon 0.2 0.0 0.7 0.0 1.0 0.1

orange 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.1 0.0 0.8

Along the top are our actual classes and down the side are our predicted classes - so counting down the columns we can get the Classification Accuracy (%) for each class, and we can see where it is getting confused.

So, while overall our test set accuracy was 75% - for each individual class we see:

- Apple: 80%

- Avocado: 100%

- Banana: 20%

- Kiwi: 70%

- Lemon: 100%

- Orange: 80%

This is very powerful - we now can see what exactly is driving our overall Classification Accuracy.

The standout insight here is for Bananas - with a 20% Classification Accuracy, and even more interestingly we can see where it is getting confused. The network predicted 70% of Banana images to be of the class Lemon!

Tackling Overfitting With Dropout

Dropout Overview

Dropout is a technique used in Deep Learning primarily to reduce the effects of over-fitting. Over-fitting is where the network learns the patterns of the training data so specifically, that it runs the risk of not generalising well, and being very unreliable when used to predict on new, unseen data.

Dropout works in a way where, for each batch of observations that is sent forwards through the network, a pre-specified proportion of the neurons in a hidden layer are essentially ignored or deactivated. This can be applied to any number of the hidden layers.

When we apply Dropout, the deactivated neurons are completely taken out of the picture - they take no part in the passing of information through the network.

All the math is the same, the network will process everything as it always would (so taking the sum of the inputs multiplied by the weights, and adding a bias term, applying activation functions, and updating the network’s parameters using Back Propagation) - it’s just that in this scenario where we are disregarding some of the neurons, we’re essentially pretending that they’re not there.

In a full network (i.e. where Dropout is not being applied) each of the combinations of neurons becomes quite specific at what it represents, at least in terms of predicting the output. At a high level, if we were classifying pictures of cats and dogs, there might be some linked combination of neurons that fires when it sees pointy ears and a long tongue. This combination of neurons becomes very tuned into its role in prediction, and it becomes very good at what it does - but as is the definition of overfitting, it becomes too good - it becomes too rigidly aligned with the training data.

If we drop out neurons during training, other neurons need to jump in fill in for this particular role of detecting those features. They essentially have to come in at late notice and cover the ignored neurons job, dealing with that particular representation that is so useful for prediction.

Over time, with different combinations of neurons being ignored for each mini-batch of data - the network becomes more adept at generalising and thus is less likely to overfit to the training data. Since no particular neuron can rely on the presence of other neurons, and the features with which they represent - the network learns more robust features, and are less susceptible to noise.

In a Convolutional Neural Network, such as in our task here - it is generally best practice to only apply Dropout to the Dense (Fully Connected) layer or layers, rather than to the Convolutional Layers.

Updated Network Architecture

In our task here, we only have one Dense Layer, so we apply Dropout to that layer only. A common proportion to apply (i.e. the proportion of neurons in the layer to be deactivated randomly each pass) is 0.5 or 50%. We will apply this here.

model = Sequential()

model.add(Conv2D(filters = 32, kernel_size = (3, 3), padding = 'same', input_shape = (img_width, img_height, num_channels)))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(MaxPooling2D())

model.add(Conv2D(filters = 32, kernel_size = (3, 3), padding = 'same'))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(MaxPooling2D())

model.add(Flatten())

model.add(Dense(32))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(Dropout(0.5))

model.add(Dense(num_classes))

model.add(Activation('softmax'))

Training The Updated Network

We run the exact same code to train this updated network as we did for the baseline network (50 epochs) - the only change is that we modify the filename for the saved network to ensure we have all network files for comparison.

Analysis Of Training Results

As we again saved our training process to the history object, we can now analyse & plot the performance (Classification Accuracy, and Loss) of the updated network epoch by epoch.

With the baseline network we saw very strong overfitting in action - it will be interesting to see if the addition of Dropout has helped!

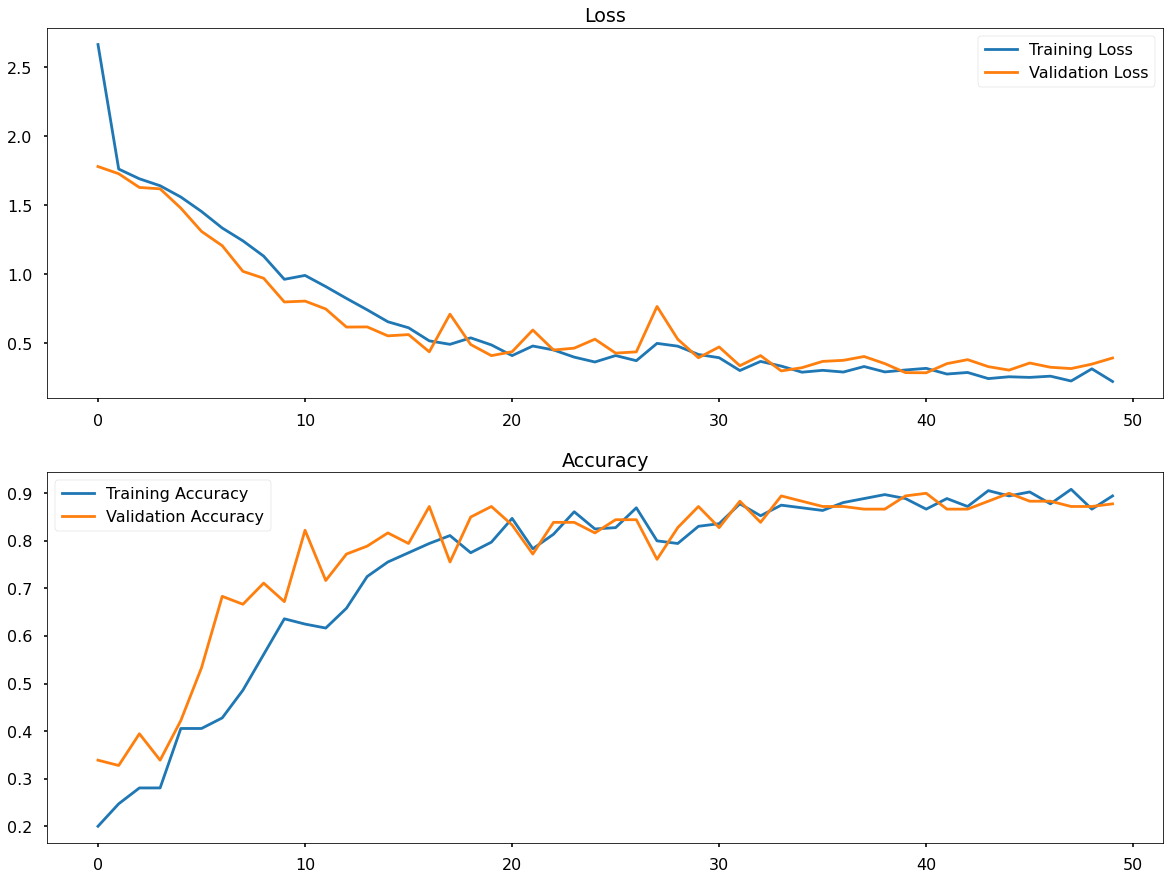

The below image shows the same two plots we analysed for the updated network, the first showing the epoch by epoch Loss for both the training set (blue) and the validation set (orange) & the second show the epoch by epoch Classification Accuracy again, for both the training set (blue) and the validation set (orange).

Firstly, we can see a peak Classification Accuracy on the validation set of around 89% which is higher than the 83% we saw for the baseline network.

Secondly, and what we were really looking to see, is that gap between the Classification Accuracy on the training set, and the validation set has been mostly eliminated. The two lines are trending up at more or less the same rate across all epochs of training - and the accuracy on the training set also never reach 100% as it did before meaning that we are indeed seeing this generalisation that we want!

The addition of Dropout does appear to have remedied the overfitting that we saw in the baseline network. This is because, while some neurons are turned off during each mini-batch iteration of training - all will have their turn, many times, to be updated - just in a way where no neuron, or combination of neurons will become so hard-wired to certain features found in the training data!

Performance On The Test Set

During training, we assessed our updated networks performance on both the training set and the validation set. Here, like we did for the baseline network, we will get a view of how well our network performs when predict on data that was no part of the training process whatsoever - our test set.

We run the exact same code as we did for the baseline network, with the only change being to ensure we are loading in network file for the updated network

Test Set Classification Accuracy

Our baseline network achieved a 75% Classification Accuracy on the test set. With the addition of Dropout we saw both a reduction in overfitting, and an increased validation set accuracy. On the test set, we again see an increase vs. the baseline, with an 85% Classification Accuracy.

Test Set Confusion Matrix

As mentioned above, while overall Classification Accuracy is very useful, but it can hide what is really going on with the network’s predictions!

The standout insight for the baseline network was that Bananas has only a 20% Classification Accuracy, very frequently being confused with Lemons. It will be interesting to see if the extra generalisation forced upon the network with the application of Dropout helps this.

Running the same code from the baseline section on results for our updated network, we get the following output:

actual_label apple avocado banana kiwi lemon orange

predicted_label

apple 0.8 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

avocado 0.0 1.0 0.1 0.2 0.0 0.0

banana 0.0 0.0 0.7 0.0 0.0 0.0

kiwi 0.2 0.0 0.0 0.7 0.0 0.1

lemon 0.0 0.0 0.2 0.0 1.0 0.0

orange 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.1 0.0 0.9

Along the top are our actual classes and down the side are our predicted classes - so counting down the columns we can get the Classification Accuracy (%) for each class, and we can see where it is getting confused.

So, while overall our test set accuracy was 85% - for each individual class we see:

- Apple: 80%

- Avocado: 100%

- Banana: 70%

- Kiwi: 70%

- Lemon: 100%

- Orange: 90%

All classes here are being predicted at least as good as with the baseline network - and Bananas which had only a 20% Classification Accuracy last time, are now being classified correctly 70% of the time. Still the lowest of all classes, but a significant improvement over the baseline network!

Image Augmentation

Image Augmentation Overview

Image Augmentation is a concept in Deep Learning that aims to not only increase predictive performance, but also to increase the robustness of the network through regularisation.

Instead of passing in each of the training set images as it stands, with Image Augmentation we pass in many transformed versions of each image. This results in increased variation within our training data (without having to explicitly collect more images) meaning the network has a greater chance to understand and learn the objects we’re looking to classify, in a variety of scenarios.

Common transformation techniques are:

- Rotation

- Horizontal/Vertical Shift

- Shearing

- Zoom

- Horizontal/Vertical Flipping

- Brightness Alteration

When applying Image Augmentation using Keras’ ImageDataGenerator class, we do this “on-the-fly” meaning the network does not actually train on the original training set image, but instead on the generated/transformed versions of the image - and this version changes each epoch. In other words - for each epoch that the network is trained, each image will be called upon, and then randomly transformed based upon the specified parameters - and because of this variation, the network learns to generalise a lot better for many different scenarios.

Implementing Image Augmentation

We apply the Image Augmentation logic into the ImageDataGenerator class that exists within our Data Pipeline.

It is important to note is that we only ever do this for our training data, we don’t apply any transformation on our validation or test sets. The reason for this is that we want our validation & test data be static, and serve us better for measuring our performance over time. If the images in these set kept changing because of transformations it would be really hard to understand if our network was actually improving, or if it was just a lucky set of validation set transformations that made it appear that is was performing better!

When setting up and training the baseline & Dropout networks - we used the ImageGenerator class for only one thing, to rescale the pixel values. Now we will add in the Image Augmentation parameters as well, meaning that as images flow into our network for training the transformations will be applied.

In the code below, we add these transformations in and specify the magnitudes that we want each applied:

# image generators

training_generator = ImageDataGenerator(rescale = 1./255,

rotation_range = 20,

width_shift_range = 0.2,

height_shift_range = 0.2,

zoom_range = 0.1,

horizontal_flip = True,

brightness_range = (0.5,1.5),

fill_mode = 'nearest')

validation_generator = ImageDataGenerator(rescale = 1./255)

We apply a rotation_range of 20. This is the degrees of rotation, and it dictates the maximum amount of rotation that we want. In other words, a rotation value will be randomly selected for each image, each epoch, between negative and positive 20 degrees, and whatever is selected, is what will be applied.

We apply a width_shift_range and a height_shift_range of 0.2. These represent the fraction of the total width and height that we are happy to shift - in other words we’re allowing Keras to shift our image up to 20% both vertically and horizonally.

We apply a zoom_range of 0.1, meaning a maximum of 10% inward or outward zoom.

We specify horizontal_flip to be True, meaning that each time an image flows in, there is a 50/50 chance of it being flipped.

We specify a brightness_range between 0.5 and 1.5 meaning our images can become brighter or darker.

Finally, we have fill_mode set to “nearest” which will mean that when images are shifted and/or rotated, we’ll just use the nearest pixel to fill in any new pixels that are required - and it means our images still resemble the scene, generally speaking!

Again, it is important to note that these transformations are applied only to the training set, and not the validation set.

Updated Network Architecture

Our network will be the same as the baseline network. We will not apply Dropout here to ensure we can understand the true impact of Image Augmentation for our task.

Training The Updated Network

We run the exact same code to train this updated network as we did for the baseline network (50 epochs) - the only change is that we modify the filename for the saved network to ensure we have all network files for comparison.

Analysis Of Training Results

As we again saved our training process to the history object, we can now analyse & plot the performance (Classification Accuracy, and Loss) of the updated network epoch by epoch.

With the baseline network we saw very strong overfitting in action - it will be interesting to see if the addition of Image Augmentation helps in the same way that Dropout did!

The below image shows the same two plots we analysed for the updated network, the first showing the epoch by epoch Loss for both the training set (blue) and the validation set (orange) & the second show the epoch by epoch Classification Accuracy again, for both the training set (blue) and the validation set (orange).

Firstly, we can see a peak Classification Accuracy on the validation set of around 97% which is higher than the 83% we saw for the baseline network, and higher than the 89% we saw for the network with Dropout added.

Secondly, and what we were again really looking to see, is that gap between the Classification Accuracy on the training set, and the validation set has been mostly eliminated. The two lines are trending up at more or less the same rate across all epochs of training - and the accuracy on the training set also never reach 100% as it did before meaning that Image Augmentation is also giving the network this generalisation that we want!

The reason for this is that the network is getting a slightly different version of each image each epoch during training, meaning that while it’s learning features, it can’t cling to a single version of those features!

Performance On The Test Set

During training, we assessed our updated networks performance on both the training set and the validation set. Here, like we did for the baseline & Dropout networks, we will get a view of how well our network performs when predict on data that was no part of the training process whatsoever - our test set.

We run the exact same code as we did for the earlier networks, with the only change being to ensure we are loading in network file for the updated network

Test Set Classification Accuracy

Our baseline network achieved a 75% Classification Accuracy on the test set, and our network with Dropout applied achieved 85%. With the addition of Image Augmentation we saw both a reduction in overfitting, and an increased validation set accuracy. On the test set, we again see an increase vs. the baseline & Dropout, with a 93% Classification Accuracy.

Test Set Confusion Matrix

As mentioned above, while overall Classification Accuracy is very useful, but it can hide what is really going on with the network’s predictions!

The standout insight for the baseline network was that Bananas has only a 20% Classification Accuracy, very frequently being confused with Lemons. Dropout, through the additional generalisation forced upon the network, helped a lot - let’s see how our network with Image Augmentation fares!

Running the same code from the baseline section on results for our updated network, we get the following output:

actual_label apple avocado banana kiwi lemon orange

predicted_label

apple 0.9 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

avocado 0.0 1.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

banana 0.1 0.0 0.8 0.0 0.0 0.0

kiwi 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.9 0.0 0.0

lemon 0.0 0.0 0.2 0.0 1.0 0.0

orange 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.1 0.0 1.0

Along the top are our actual classes and down the side are our predicted classes - so counting down the columns we can get the Classification Accuracy (%) for each class, and we can see where it is getting confused.

So, while overall our test set accuracy was 93% - for each individual class we see:

- Apple: 90%

- Avocado: 100%

- Banana: 80%

- Kiwi: 90%

- Lemon: 100%

- Orange: 100%

All classes here are being predicted more accurately when compared to the baseline network, and at least as accurate or better when compared to the network with Dropout added.

Utilising Image Augmentation and applying Dropout will be a powerful combination!

Hyper-Parameter Tuning

Keras Tuner Overview

So far, with our Fruit Classification task, we have:

- Started with a baseline model

- Added Dropout to help with overfitting

- Utilised Image Augmentation

The addition of Dropout, and Image Augmentation boosted both performance and robustness - but there is one thing we’ve not tinkered with yet, and something that could have a big impact on how well the network learns to find and utilise important features for classifying our fruits - and that is the network architecture!

So far, we’ve just used 2 convolutional layers, each with 32 filters, and we’ve used a single Dense layer, also, just by coincidence, with 32 neurons - and we admitted that this was just a place to start, our baseline.

One way for us to figure out if there are better architectures, would be to just try different things. Maybe we just double our number of filters to 64, or maybe we keep the first convolutional layer at 32, but we increase the second to 64.Perhaps we put a whole lot of neurons in our hidden layer, and then, what about things like our use of Adam as an optimizer, is this the best one for our particular problem, or should we use something else?

As you can imagine, we could start testing all of these things, and noting down performances, but that would be quite messy.

Here we will instead utlise Keras Tuner which will make this a whole lot easier for us!

At a high level, with Keras Tuner, we will ask it to test, a whole host of different architecture and parameter options, based upon some specifications that we put in place. It will go off and run some tests, and return us all sorts of interesting summary statistics, and of course information about what worked best.

Once we have this, we can then create that particular architecture, train the network just as we’ve always done - and analyse the performance against our original networks.

Our data pipeline will remain the same as it was when applying Image Augmentation. The code below shows this, as well as the extra packages we need to load for Keras-Tuner.

# import the required python libraries

from tensorflow.keras.models import Sequential

from tensorflow.keras.layers import Conv2D, MaxPooling2D, Activation, Flatten, Dense, Dropout

from tensorflow.keras.preprocessing.image import ImageDataGenerator

from tensorflow.keras.callbacks import ModelCheckpoint

from keras_tuner.tuners import RandomSearch

from keras_tuner.engine.hyperparameters import HyperParameters

import os

# data flow parameters

training_data_dir = 'data/training'

validation_data_dir = 'data/validation'

batch_size = 32

img_width = 128

img_height = 128

num_channels = 3

num_classes = 6

# image generators

training_generator = ImageDataGenerator(rescale = 1./255)

validation_generator = ImageDataGenerator(rescale = 1./255)

# image flows

training_set = training_generator.flow_from_directory(directory = training_data_dir,

target_size = (img_width, img_height),

batch_size = batch_size,

class_mode = 'categorical')

validation_set = validation_generator.flow_from_directory(directory = validation_data_dir,

target_size = (img_width, img_height),

batch_size = batch_size,

class_mode = 'categorical')

Application Of Keras Tuner

Here we specify what we want Keras Tuner to test, and how we want it to test it!

We put our network architecture into a function with a single parameter called hp (hyperparameter)

We then make use of several in-build bits of logic to specify what we want to test. In the code below we test for:

- Convolutional Layer Count - Between 1 & 4

- Convolutional Layer Filter Count - Between 32 & 256 (Step Size 32)

- Dense Layer Count - Between 1 & 4

- Dense Layer Neuron Count - Between 32 & 256 (Step Size 32)

- Application Of Dropout - Yes or No

- Optimizer - Adam or RMSProp

# network architecture

def build_model(hp):

model = Sequential()

model.add(Conv2D(filters = hp.Int("Input_Conv_Filters", min_value = 32, max_value = 256, step = 32), kernel_size = (3, 3), padding = 'same', input_shape = (img_width, img_height, num_channels)))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(MaxPooling2D())

for i in range(hp.Int("n_Conv_Layers", min_value = 1, max_value = 3, step = 1)):

model.add(Conv2D(filters = hp.Int(f"Conv_{i}_Filters", min_value = 32, max_value = 256, step = 32), kernel_size = (3, 3), padding = 'same'))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(MaxPooling2D())

model.add(Flatten())

for j in range(hp.Int("n_Dense_Layers", min_value = 1, max_value = 4, step = 1)):

model.add(Dense(hp.Int(f"Dense_{j}_Neurons", min_value = 32, max_value = 256, step = 32)))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

if hp.Boolean("Dropout"):

model.add(Dropout(0.5))

model.add(Dense(num_classes))

model.add(Activation('softmax'))

# compile network

model.compile(loss = 'categorical_crossentropy',

optimizer = hp.Choice("Optimizer", values = ['adam', 'RMSProp']),

metrics = ['accuracy'])

return model

Once we have the testing logic in place - we use want to put in place the specifications for the search!

In the code below, we set parameters to:

- Point to the network function with the testing logic (hypermodel)

- Set the metric to optimise for (objective)

- Set the number of random network configurations to test (max_trials)

- Set the number of times to try each tested configuration (executions_per_trial)

- Set the details for the output of logging & results

# search parameters

tuner = RandomSearch(hypermodel = build_model,

objective = 'val_accuracy',

max_trials = 30,

executions_per_trial = 2,

directory = os.path.normpath('C:/'),

project_name = 'fruit-cnn',

overwrite = True)

With the search parameters in place, we now want to put this into action.

In the below code, we:

- Specify the training & validation flows

- Specify the number of epochs for each tested configuration

- Specify the batch size for training

# execute search

tuner.search(x = training_set,

validation_data = validation_set,

epochs = 40,

batch_size = 32)

Depending on how many configurations are to be tested, how many epochs are required for each, and the speed of processing - this can take a long time, but the results will most definitely guide us towards a more optimal architecture!

Updated Network Architecture

Based upon the tested network architectures, the best in terms of validation accuracy was one that contains 3 Convolutional Layers. The first has 96 filters and the subsequent two each 64 filters. Each of these layers have an accompanying MaxPooling Layer (this wasn’t tested). The network then has 1 Dense (Fully Connected) Layer following flattening with 160 neurons with Dropout applied - followed by our output layer. The chosen optimizer was Adam.

# network architecture

model = Sequential()

model.add(Conv2D(filters = 96, kernel_size = (3, 3), padding = 'same', input_shape = (img_width, img_height, num_channels)))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(MaxPooling2D())

model.add(Conv2D(filters = 64, kernel_size = (3, 3), padding = 'same'))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(MaxPooling2D())

model.add(Conv2D(filters = 64, kernel_size = (3, 3), padding = 'same'))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(MaxPooling2D())

model.add(Flatten())

model.add(Dense(160))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(Dropout(0.5))

model.add(Dense(num_classes))

model.add(Activation('softmax'))

# compile network

model.compile(loss = 'categorical_crossentropy',

optimizer = 'adam',

metrics = ['accuracy'])

The below shows us more clearly our optimised architecture:

_________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

=================================================================

conv2d_10 (Conv2D) (None, 128, 128, 96) 2688

_________________________________________________________________

activation_20 (Activation) (None, 128, 128, 96) 0

_________________________________________________________________

max_pooling2d_10 (MaxPooling (None, 64, 64, 96) 0

_________________________________________________________________

conv2d_11 (Conv2D) (None, 64, 64, 64) 55360

_________________________________________________________________

activation_21 (Activation) (None, 64, 64, 64) 0

_________________________________________________________________

max_pooling2d_11 (MaxPooling (None, 32, 32, 64) 0

_________________________________________________________________

conv2d_12 (Conv2D) (None, 32, 32, 64) 36928

_________________________________________________________________

activation_22 (Activation) (None, 32, 32, 64) 0

_________________________________________________________________

max_pooling2d_12 (MaxPooling (None, 16, 16, 64) 0

_________________________________________________________________

flatten_5 (Flatten) (None, 16384) 0

_________________________________________________________________

dense_10 (Dense) (None, 160) 2621600

_________________________________________________________________

activation_23 (Activation) (None, 160) 0

_________________________________________________________________

dropout_3 (Dropout) (None, 160) 0

_________________________________________________________________

dense_11 (Dense) (None, 6) 966

_________________________________________________________________

activation_24 (Activation) (None, 6) 0

=================================================================

Total params: 2,717,542

Trainable params: 2,717,542

Non-trainable params: 0

_________________________________________________________________

Our optimised architecture has a total of 2.7 million parameters, a step up from 1.1 million in the baseline architecture.

Training The Updated Network

We run the exact same code to train this updated network as we did for the baseline network (50 epochs) - the only change is that we modify the filename for the saved network to ensure we have all network files for comparison.

Analysis Of Training Results

As we again saved our training process to the history object, we can now analyse & plot the performance (Classification Accuracy, and Loss) of the updated network epoch by epoch.

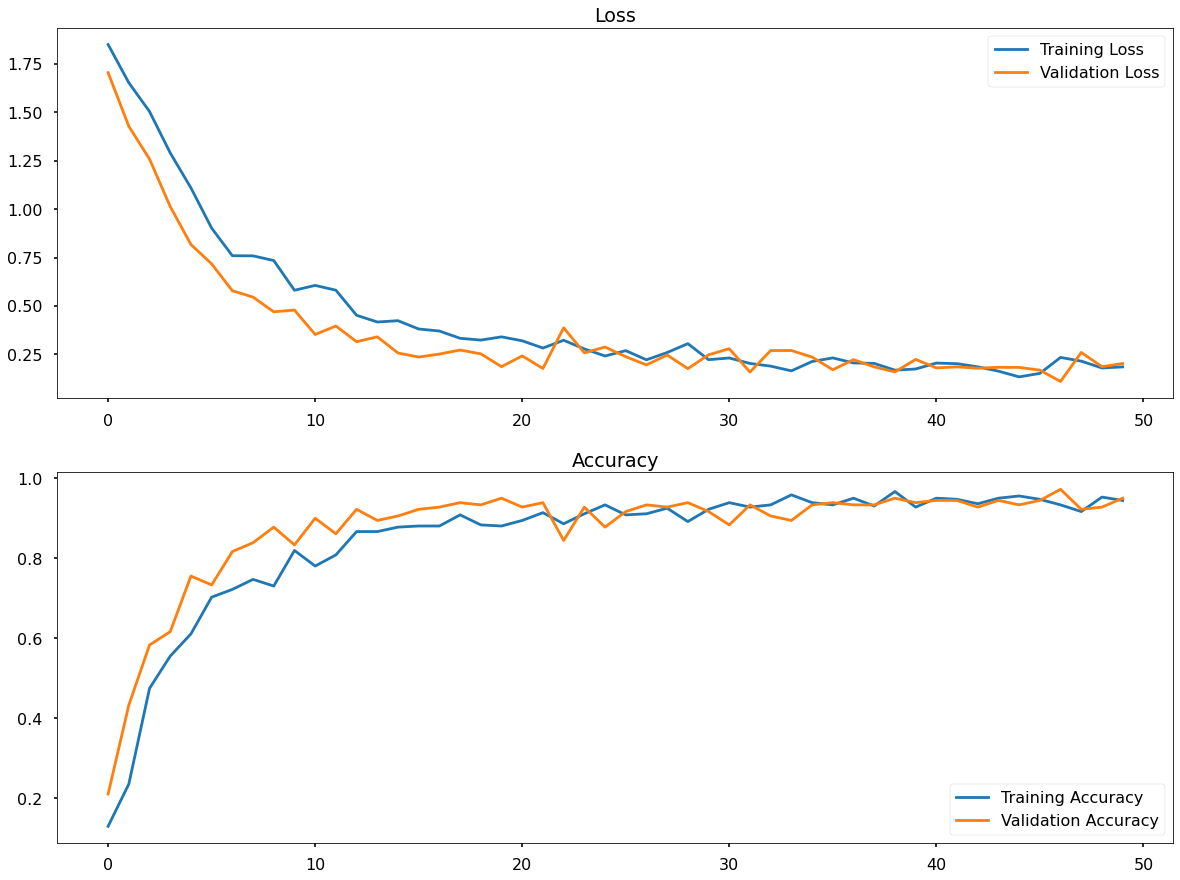

The below image shows the same two plots we analysed for the tuned network, the first showing the epoch by epoch Loss for both the training set (blue) and the validation set (orange) & the second show the epoch by epoch Classification Accuracy again, for both the training set (blue) and the validation set (orange).

Firstly, we can see a peak Classification Accuracy on the validation set of around 98% which is the highest we have seen from all networks so far, just higher than the 97% we saw for the addition of Image Augmentation to our baseline network.

As Dropout & Image Augmentation are in place here, we again see the elimination of overfitting.

Performance On The Test Set

During training, we assessed our updated networks performance on both the training set and the validation set. Here, like we did for the baseline & Dropout networks, we will get a view of how well our network performs when predict on data that was no part of the training process whatsoever - our test set.

We run the exact same code as we did for the earlier networks, with the only change being to ensure we are loading in network file for the updated network

Test Set Classification Accuracy

Our optimised network, with both Dropout & Image Augmentation in place, scored 95% on the Test Set, again marginally higher than what we had seen from the other networks so far.

Test Set Confusion Matrix

As mentioned each time, while overall Classification Accuracy is very useful, but it can hide what is really going on with the network’s predictions!

Our 95% Test Set accuracy at an overall level tells us that we don’t have too much to worry about here, but let’s take a look anyway and see if anything interesting pops up.

Running the same code from the baseline section on results for our updated network, we get the following output:

actual_label apple avocado banana kiwi lemon orange

predicted_label

apple 0.9 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

avocado 0.0 1.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

banana 0.0 0.0 0.9 0.0 0.0 0.0

kiwi 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.9 0.0 0.0

lemon 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.0 0.0

orange 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.1 0.0 1.0

Along the top are our actual classes and down the side are our predicted classes - so counting down the columns we can get the Classification Accuracy (%) for each class, and we can see where it is getting confused.

So, while overall our test set accuracy was 95% - for each individual class we see:

- Apple: 90%

- Avocado: 100%

- Banana: 90%

- Kiwi: 90%

- Lemon: 100%

- Orange: 100%

All classes here are being predicted at least as accurate or better when compared to the best network so far - so our optimised architecture does appear to have helped!

Transfer Learning With VGG16

Transfer Learning Overview

Transfer Learning is an extremely powerful way for us to utilise pre-built, and pre-trained networks, and apply these in a clever way to solve our specific Deep Learning based tasks. It consists of taking features learned on one problem, and leveraging them on a new, similar problem!

For image based tasks this often means using all the the pre-learned features from a large network, so all of the convolutional filter values and feature maps, and instead of using it to predict what the network was originally designed for, piggybacking it, and training just the last part for some other task.

The hope is, that the features which have already been learned will be good enough to differentiate between our new classes, and we’ll save a whole lot of training time (and be able to utilise a network architecture that has potentially already been optimised).

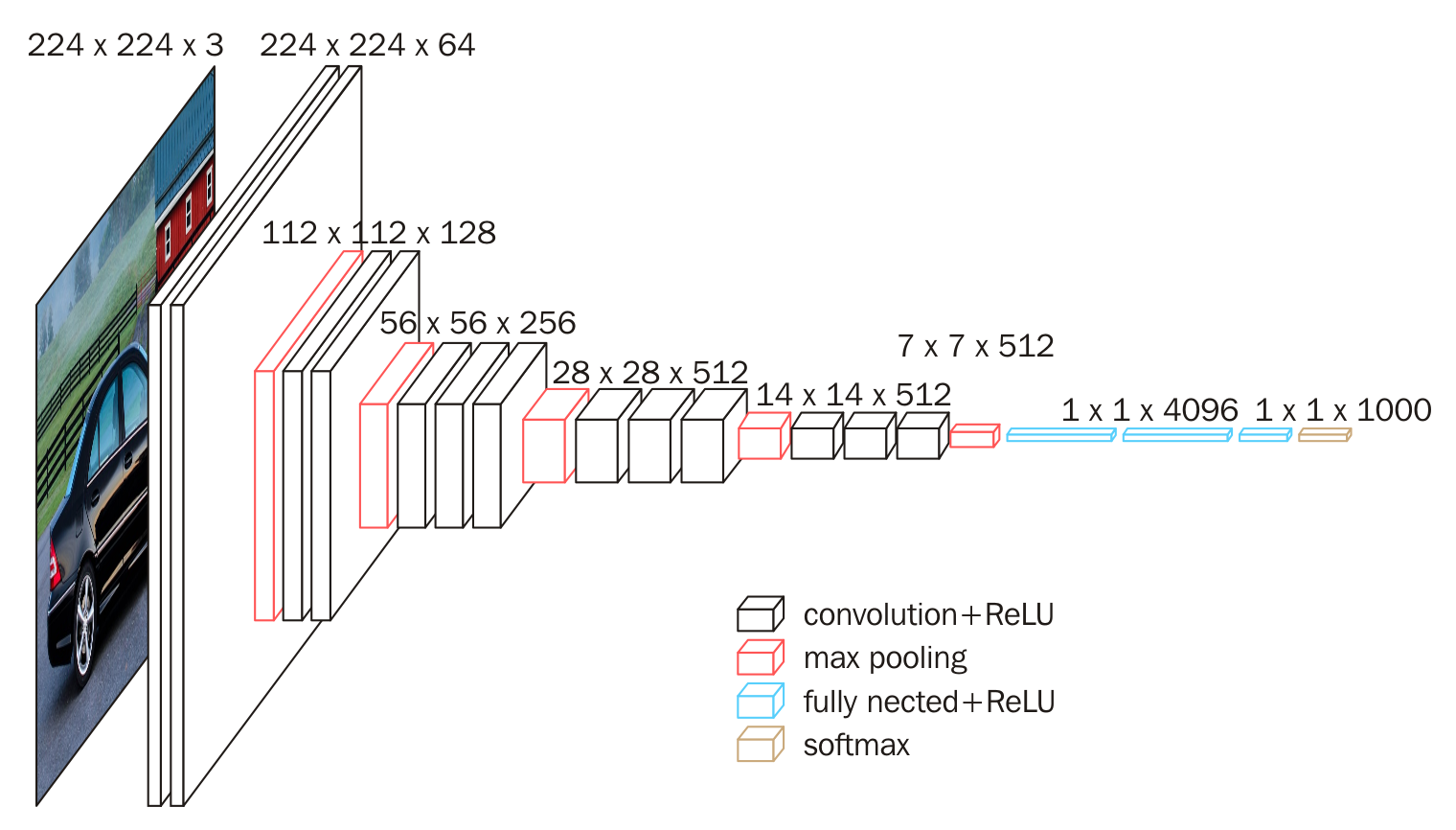

For our Fruit Classification task we will be utilising a famous network known as VGG16. This was designed back in 2014, but even by todays standards is a fairly heft network. It was trained on the famous ImageNet dataset, with over a million images across one thousand different image classes. Everything from goldfish to cauliflowers to bottles of wine, to scuba divers!

The VGG16 network won the 2014 ImageNet competition, meaning that it predicted more accurately than any other model on that set of images (although this has now been surpassed).

If we can get our hands on the fully trained VGG16 model object, built to differentiate between all of those one thousand different image classes, the features that are contained in the layer prior to flattening will be very rich, and could be very useful for predicting all sorts of other images too without having to (a) re-train this entire architecture, which would be computationally, very expensive or (b) having to come up with our very own complex architecture, which we know can take a lot of trial and error to get right!

All the hard work has been done, we just want to “transfer” those “learnings” to our own problem space.

Updated Data Pipeline

Our data pipeline will remain mostly the same as it was when applying our own custom built networks - but there are some subtle changes. In the code below we need to import VGG16 and the custom preprocessing logic that it uses. We also need to send our images in with the size 224 x 224 pixels as this is what VGG16 expects. Otherwise, the logic stays as is.

# import the required python libraries

from tensorflow.keras.models import Model

from tensorflow.keras.layers import Activation, Flatten, Dense, Dropout

from tensorflow.keras.preprocessing.image import ImageDataGenerator

from tensorflow.keras.callbacks import ModelCheckpoint

from tensorflow.keras.applications.vgg16 import VGG16, preprocess_input

# data flow parameters

training_data_dir = 'data/training'

validation_data_dir = 'data/validation'

batch_size = 32

img_width = 224

img_height = 224

num_channels = 3

num_classes = 6

# image generators

training_generator = ImageDataGenerator(preprocessing_function = preprocess_input,

rotation_range = 20,

width_shift_range = 0.2,

height_shift_range = 0.2,

zoom_range = 0.1,

horizontal_flip = True,

brightness_range = (0.5,1.5),

fill_mode = 'nearest')

validation_generator = ImageDataGenerator(rescale = 1./255)

# image flows

training_set = training_generator.flow_from_directory(directory = training_data_dir,

target_size = (img_width, img_height),

batch_size = batch_size,

class_mode = 'categorical')

validation_set = validation_generator.flow_from_directory(directory = validation_data_dir,

target_size = (img_width, img_height),

batch_size = batch_size,

class_mode = 'categorical')

Network Architecture

Keras makes the use of VGG16 very easy. We will download the bottom of the VGG16 network (everything up to the Dense Layers) and add in what we need to apply the top of the model to our fruit classes.

We then need to specify that we do not want the imported layers to be re-trained, we want their parameters values to be frozen.

The original VGG16 network architecture contains two massive Dense Layers near the end, each with 4096 neurons. Since our task of classiying 6 types of fruit is more simplistic than the original 1000 ImageNet classes, we reduce this down and instead implement two Dense Layers with 128 neurons each, followed by our output layer.

# network architecture

vgg = VGG16(input_shape = (img_width, img_height, num_channels), include_top = False)

# freeze all layers (they won't be updated during training)

for layer in vgg.layers:

layer.trainable = False

flatten = Flatten()(vgg.output)

dense1 = Dense(128, activation = 'relu')(flatten)

dense2 = Dense(128, activation = 'relu')(dense1)

output = Dense(num_classes, activation = 'softmax')(dense2)

model = Model(inputs = vgg.inputs, outputs = output)

# compile network

model.compile(loss = 'categorical_crossentropy',

optimizer = 'adam',

metrics = ['accuracy'])

# view network architecture

model.summary()

The below shows us our final architecture:

_________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

=================================================================

input_1 (InputLayer) [(None, 224, 224, 3)] 0

_________________________________________________________________

block1_conv1 (Conv2D) (None, 224, 224, 64) 1792

_________________________________________________________________

block1_conv2 (Conv2D) (None, 224, 224, 64) 36928

_________________________________________________________________

block1_pool (MaxPooling2D) (None, 112, 112, 64) 0

_________________________________________________________________

block2_conv1 (Conv2D) (None, 112, 112, 128) 73856

_________________________________________________________________

block2_conv2 (Conv2D) (None, 112, 112, 128) 147584

_________________________________________________________________

block2_pool (MaxPooling2D) (None, 56, 56, 128) 0

_________________________________________________________________

block3_conv1 (Conv2D) (None, 56, 56, 256) 295168

_________________________________________________________________

block3_conv2 (Conv2D) (None, 56, 56, 256) 590080

_________________________________________________________________

block3_conv3 (Conv2D) (None, 56, 56, 256) 590080

_________________________________________________________________

block3_pool (MaxPooling2D) (None, 28, 28, 256) 0

_________________________________________________________________

block4_conv1 (Conv2D) (None, 28, 28, 512) 1180160

_________________________________________________________________

block4_conv2 (Conv2D) (None, 28, 28, 512) 2359808

_________________________________________________________________

block4_conv3 (Conv2D) (None, 28, 28, 512) 2359808

_________________________________________________________________

block4_pool (MaxPooling2D) (None, 14, 14, 512) 0

_________________________________________________________________

block5_conv1 (Conv2D) (None, 14, 14, 512) 2359808

_________________________________________________________________

block5_conv2 (Conv2D) (None, 14, 14, 512) 2359808

_________________________________________________________________

block5_conv3 (Conv2D) (None, 14, 14, 512) 2359808

_________________________________________________________________

block5_pool (MaxPooling2D) (None, 7, 7, 512) 0

_________________________________________________________________

flatten_7 (Flatten) (None, 25088) 0

_________________________________________________________________

dense_14 (Dense) (None, 128) 3211392

_________________________________________________________________

dense_15 (Dense) (None, 128) 16512

_________________________________________________________________

dense_16 (Dense) (None, 6) 774

=================================================================

Total params: 17,943,366

Trainable params: 3,228,678

Non-trainable params: 14,714,688

_________________________________________________________________

Our VGG16 architecture has a total of 17.9 million parameters, much bigger than what we have built so far. Of this, 14.7 million parameters are frozen, and 3.2 million parameters will be updated during each iteration of back-propagation, and these are going to be figuring out exactly how to use those frozen parameters that were learned from the ImageNet dataset, to predict our classes of fruit!

Training The Network

We run the exact same code to train this updated network as we did for the baseline network, although to start with for only 10 epochs as it is a much more computationally expensive training process.

Analysis Of Training Results

As we again saved our training process to the history object, we can now analyse & plot the performance (Classification Accuracy, and Loss) of the updated network epoch by epoch.

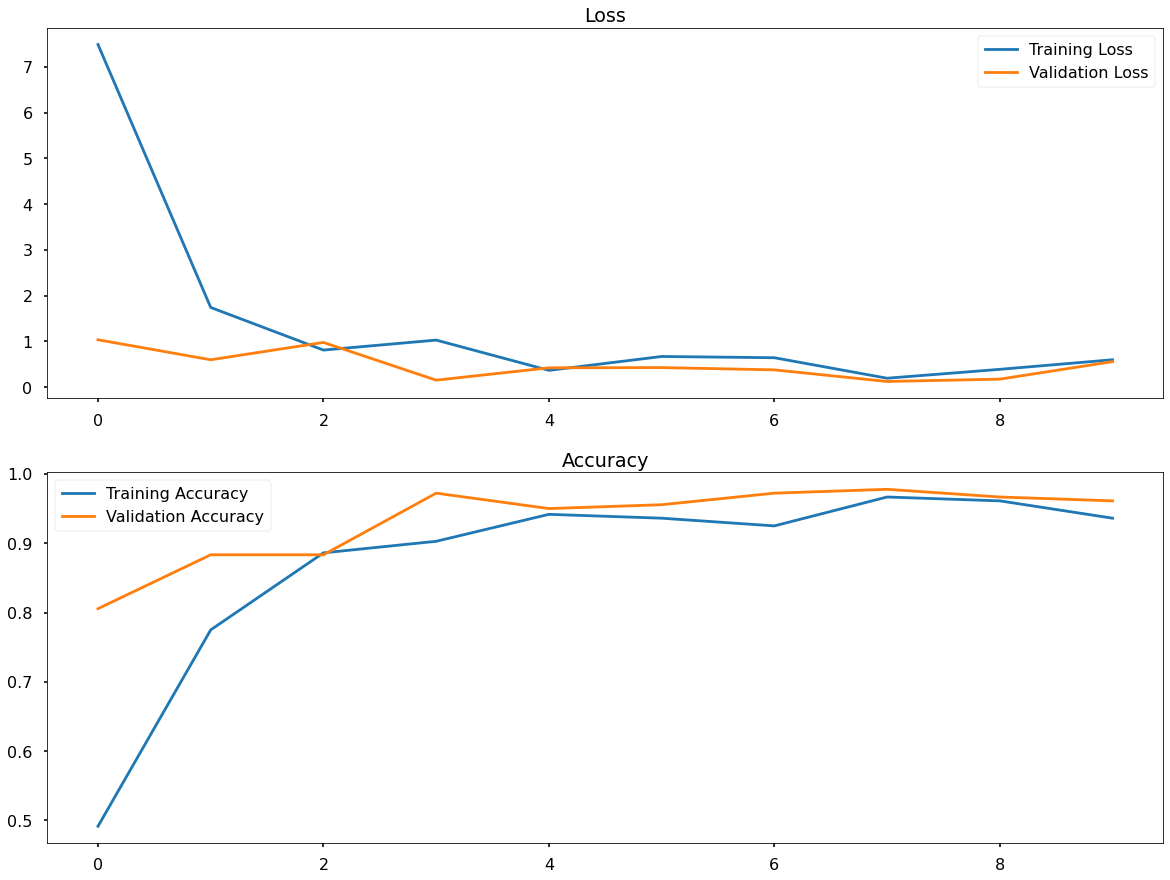

The below image shows the same two plots we analysed for the tuned network, the first showing the epoch by epoch Loss for both the training set (blue) and the validation set (orange) & the second show the epoch by epoch Classification Accuracy again, for both the training set (blue) and the validation set (orange).

Firstly, we can see a peak Classification Accuracy on the validation set of around 98% which is equal to the highest we have seen from all networks so far, but what is impressive is that it achieved this in only 10 epochs!

Performance On The Test Set

During training, we assessed our updated networks performance on both the training set and the validation set. Here, like we did for all other networks, we will get a view of how well our network performs when predict on data that was no part of the training process whatsoever - our test set.

We run the exact same code as we did for the earlier networks, with the only change being to ensure we are loading in network file for the updated network

Test Set Classification Accuracy

Our VGG16 network scored 98% on the Test Set, higher than that of our best custom network.

Test Set Confusion Matrix

As mentioned each time, while overall Classification Accuracy is very useful, but it can hide what is really going on with the network’s predictions!

Our 98% Test Set accuracy at an overall level tells us that we don’t have too much to worry about here, but for comparisons sake let’s take a look!

Running the same code from the baseline section on results for our updated network, we get the following output:

actual_label apple avocado banana kiwi lemon orange

predicted_label

apple 1.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

avocado 0.0 1.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

banana 0.0 0.0 1.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

kiwi 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.0 0.0 0.0

lemon 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.9 0.0

orange 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.1 1.0

Along the top are our actual classes and down the side are our predicted classes - so counting down the columns we can get the Classification Accuracy (%) for each class, and we can see where it is getting confused.

So, while overall our test set accuracy was 98% - for each individual class we see:

- Apple: 100%

- Avocado: 100%

- Banana: 100%

- Kiwi: 100%

- Lemon: 90%

- Orange: 100%

All classes here are being predicted at least as accurate or better when compared to the best custom network!

Overall Results Discussion

We have made some huge strides in terms of making our network’s predictions more accurate, and more reliable on new data.

Our baseline network suffered badly from overfitting - the addition of both Dropout & Image Augmentation elimited this almost entirely.

In terms of Classification Accuracy on the Test Set, we saw:

- Baseline Network: 75%

- Baseline + Dropout: 85%

- Baseline + Image Augmentation: 93%

- Optimised Architecture + Dropout + Image Augmentation: 95%

- Transfer Learning Using VGG16: 98%

Tuning the networks architecture with Keras-Tuner gave us a great boost, but was also very time intensive - however if this time investment results in improved accuracy then it is time well spent.

The use of Transfer Learning with the VGG16 architecture was also a great success, in only 10 epochs we were able to beat the performance of our smaller, custom networks which were training over 50 epochs. From a business point of view we also need to consider the overheads of (a) storing the much larger VGG16 network file, and (b) any increased latency on inference.

Growth & Next Steps

The proof of concept was successful, we have shown that we can get very accurate predictions albeit on a small number of classes. We need to showcase this to the client, discuss what it is that makes the network more robust, and then look to test our best networks on a larger array of classes.

Transfer Learning has been a big success, and was the best performing network in terms of classification accuracy on the Test Set - however we still only trained for a small number of epochs so we can push this even further. It would be worthwhile testing other available pre-trained networks such as ResNet, Inception, and the DenseNet networks.